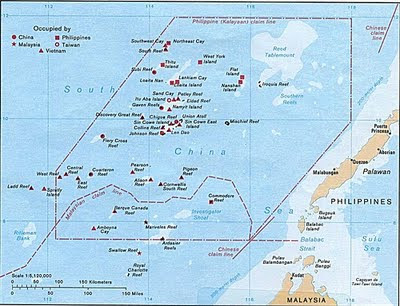

Overlapping territorial claims to the Spratly Islands by China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei have escalated the conflict in this region to a new high. China, Vietnam, and the Philippines, the three most assertive in their claims, have engaged in naval clashes before and there is prospect of more in the future.

|

| United States cruisers operate in the South China Sea. Photo by Former Navy Gallery. |

While China and Vietnam continue to flex their muscle by staging military exercises in the South China Sea, the Philippines, the weakest military-wise, is not to be outdone. With U.S. troops and naval ships under the Visiting Forces Agreement between the Philippines and the United States, both countries have been conducting their military games a few kilometres away from the disputed islands, prompting Beijing to complain that the exercises were an indirect offence to China’s sovereignty.

More than a territorial dispute

Clearly, this is more than a mere squabble over territory.

Ever since reports were published that the Spratlys may be sitting on enormous reserves of oil and natural gas, the jockeying between these three countries has never been more intense. China appears to be the most eager to lay its hands on Spratlys oil. Its booming economy needs the vast energy resources that Spratlys can provide. Vietnam and the Philippines can surely make use of Spratlys wealth to provide for their country’s needs.

|

| The disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea. Photo by Google earth. Please click the following link to view http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W-CDMSOGaRY, "The South Cina Sea: Troubled Waters." |

A 1969 United Nations report indicated probable rich hydrocarbon deposits in the Spratly Islands. The international oil industry has compared the Spratly petroleum deposit to an elephant with the potential to produce over a billion barrels of oil.

Each of the claimant countries shapes their claim on a variety of arguments, ranging from historical evidence of discovery and occupation to arguments based on international law principles and the UNCLOS provisions. Every state is sticking to their territorial claim of sovereignty, which for the most part is weak but no one is willing to budge.

The evidence presented by China, Taiwan and Vietnam to support their historical claims is unconvincing, if not dubious at most. Their evidence merely illustrates their countries’ intermittent contact and brief occupation of the islands. The same is true with the claims of the Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei which all suffer from factual weaknesses and legal misinterpretations.

Sovereignty claims are driving the Spratly Islands conflict to the edge of brinkmanship. It is now a war of words between China, the Philippines and Vietnam. This sabre-rattling must stop if they want a reasonable and equitable settlement of their dispute. Otherwise, they face the possibility of a military confrontation. In the end, whoever has control of the Spratly Islands will have hegemony in the entire region.

International case law

Two cases in international law are worth reviewing in regard to the conflicting territorial sovereignty claims over Spratly Islands.

The Island of Palmas case, decided by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1928, set forth the factors necessary in establishing territorial sovereignty over an island. In Palmas, the case is about the conflicting sovereignty claims of the United States and the Netherlands over an isolated, but inhabited island located between the Philippines and the former Dutch East Indies. The U.S. claimed that Spain originally discovered Palmas Island and subsequently ceded title to the United States under the Treaty of Paris.

The United States also based its claim on the island's contiguity to the Philippines. The Netherlands, on the other hand, claimed sovereignty based on their peaceful and continuous display of state authority over the island.

The court awarded Palmas Island to the Netherlands and held that the mere act of discovering an island results only in inchoate title and does not suffice to establish sovereignty unless the discovery is followed by a continuous and peaceful display of authority or some degree of effective occupation.

In contrast, the Permanent Court of Arbitration held in the Clipperton Island case that France's discovery and declaration of sovereignty in a Honolulu journal were sufficient to establish sovereignty over an uninhabited atoll. The court concluded that in some instances, where the territory claimed is completely uninhabited, the requirement of effective occupation may be unnecessary.

The Clipperton case involved the sovereignty claims of France and Mexico over an uninhabited atoll located off the coast of Mexico. France argued that a French Lieutenant claimed the island on behalf of the French government in 1858, while Mexico claimed ownership by way of cession from Spain.

The Clipperton Island case is relevant to the Spratly Islands dispute because the islands are similarly isolated and uninhabited. However, higher standards for effective control may be applied in the Spratly Islands dispute because of the number of claimant countries involved and the complexity of their claims. The International Court of Justice also held that when an ambiguity exists, actual displays of authority, evidence of possession, and acquiescence by other states to the exercise of sovereignty are of decisive importance in determining sovereignty issues.

Each of the countries in the Spratlys dispute has made attempts to occupy the islands. Taiwan, for example, has continuously occupied Itu Aba since 1956, and Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, China and Brunei have each controlled several features of the archipelago. These occupations most likely satisfy the Palmas standard of a continuous display of authority. Other claimant countries, however, have protested and not acquiesced to these sovereign displays.

UNCLOS has little impact

In 1982, the United Nations United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was adopted. While UNCLOS embodies customary international law and governs practically every aspect of ocean management, it is of little impact in the Spratly Islands dispute since it fails to provide specific guidelines for delimiting maritime boundaries, especially where there are overlapping claims. The only guidance UNCLOS provides is that boundary disputes involving the continental shelf or exclusive economic zone (EEZ) shall be resolved by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, to achieve an equitable solution.

Both China and Vietnam have rejected Philippine challenges to elevate the Spratly Island dispute to a special tribunal created under UNCLOS for maritime disputes or to the International Court of Justice. It is rather obvious that China and Vietnam would have difficulty substantiating the legal basis for their claims. However, China is agreeable to a joint undertaking to explore Spratlys’ natural wealth but only on a bilateral basis.

Possible joint development zone

Settlement of the Spratlys dispute by an international court or tribunal appears to be beyond the immediate horizon. The only alternative, which may work in the best interests of all the countries, would be to establish a joint development zone. Previous studies in the past have stressed the need to implement more confidence building measures among the claimant states. There was also a proposal made to establish a three-tiered joint development agreement, consisting of twelve separate joint development zones.

More than fifty years have passed, yet the settlement of Spratlys dispute appears headed nowhere. The Spratly claimants, perhaps, can learn some lessons from the negotiations over the Timor Gap, originally between Australia and Indonesia, and later between Australia and East Timor, when the latter seceded from Indonesia to become an independent state.

Originally known as the Treaty between Australia and the Republic of Indonesia on the zone of cooperation in an area between the Indonesian province of East Timor and Northern Australia, the treaty provided for the joint exploration of petroleum resources in a part of the Timor Sea seabed which was claimed by both countries. East Timor at the time was invaded by Indonesia and was annexed as its province. The negotiations between Australia and Indonesia and the ultimate signing of the treaty were criticized as Australia’s de jure recognition of the Indonesian invasion and annexation of East Timor.

Lessons from Timor

When East Timor seceded from Indonesia in 1998, a new treaty was negotiated resulting in the Timor Sea Treaty. Although the negotiations over Timor Gap had a long and complex history, Australia and independent East Timor have generally accepted that the issue of East Timor’s maritime boundary is much less important than the wealth that could be generated for the new country by the exploitation of the Timor Sea resources.

|

| Cumulative oil slick footprint in the Timor Sea, August 30, 2009. Photo by Sky Truth. Please click the following link http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-XyatkST4m8 to view "The Timor Gap - East Timor." |

The new Timor Gap Treaty which was signed on July 5, 2001, guaranteed that the East Timorese and Australian economies would both benefit from the sea’s oil resources, instead of keeping a protracted conflict over which country owns the seabed and has jurisdiction to its resources. Time will tell when the issue of sovereignty shall again arise between the two countries since no one is willing to give ground on its respective position, although anything is possible once the oil is gone.

Spratlys’ competing states could similarly opt to follow the Timor Sea Treaty framework. Exploit the archipelago’s vast reserves of oil and natural gas, share the fruits among them based on their permanent economic interests to their territorial claims, and decide on the sovereignty conflict later, perhaps after all the oil is gone.

Both international law and the UNCLOS fail to provide a definitive answer to the Spratly Islands dispute. Any solution, however, will take time. By agreeing to a provisional joint development plan that will benefit every claimant state, the countries will at least be able to jointly and equitably exploit the natural resources of Spratlys, or until they can agree on a more permanent solution.